As time progresses, it is less and less likely that the Leave voters of 2016 will ever see the fruits of their vote if they had in mind that promise of extra weekly money for the NHS in millions.

Despite the widely publicised economy of £350 million a week that was promised for the NHS, there is close to no one left to say that this figure can be achieved anytime soon. Not even those who suggested it. And with good reasons.

Where does this £350 million figure come from?

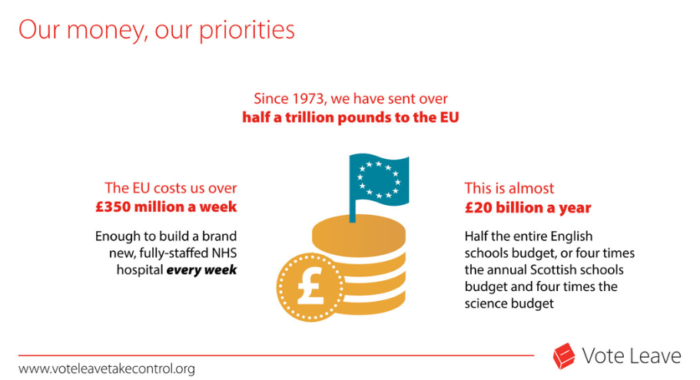

The affirmation that leaving the European Union could save the country £350 million a week and spend this money on the NHS comes from the Leave campaign of the Brexit referendum in 2016.

It stated that the UK is sending £350 million a week to be part of the European Union, and so the country could divert this amount of money by leaving the EU altogether and spend it at home instead, like on the NHS.

The Leave campaign website has now been inactive since the outcome of the referendum, and much of its content is now gone, but a cached version of the website indicates the campaign calculated this figure out of this Office for National Statistics spreadsheet (as linked below “Key Facts”).

Was it accurate?

The figure was ruled as “potentially misleading” by the UK Statistics Authority.

According to an analysis carried by the Office for National Statistics in April 2016, specifically on this issue as requested by an MP and passed on by the UK Statistics Authority, the £350 million a week seems to refer to the yearly gross contribution the UK issued in payments to the EU. These are the payments that the country is first sending to Brussels.

In 2014, this figure was estimated to be £365 million a week, or £19.1 billion for the whole year, while on average from 2010 to 2014 the annual figure was £17.4 billion, or £335 million a week.

But, as the authority insists, this figure simply took into account what the country sends to the EU but not what it received back in payments.

From the 5-year average figure of £17.4 billion, it comes down to…

- £13.9 billion when the Fontainebleau rebate is taken into account;

- £8.89 billion once the UK public sector received its EU payments; and

- £7.09 billion after payments to non-public sector bodies for various projects, or £135 million weekly.

Therefore, per week, £135 million was considered as a more accurate, non-misleading figure than the £335 million.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent and non-politically-aligned research institute came up with similarly lower figures as well.

Right. But we’re still sending more money than we are receiving?

Regarding direct, more trackable money, yes.

Britain sends more money than it receives from the EU, and the European Commission itself acknowledges it, but opines that all benefits are not measurable:

“The UK pays more into the EU budget than it receives from it. However, the net balance does not accurately reflect the many benefits of EU membership. Many of them, such as peace, political stability, security and freedom to live, work, study and travel anywhere in the Union cannot be measured,” explains the Commission’s website.

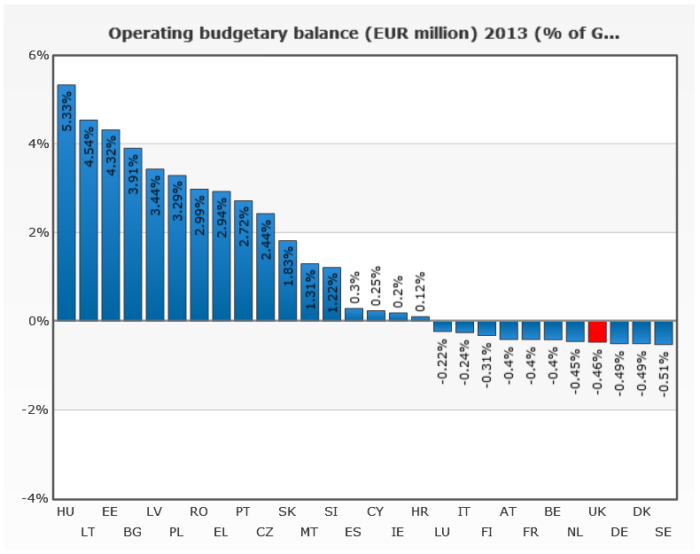

The UK is part of a smaller group of EU countries that include France, Germany, Italy Belgium, the Netherlands and a few others who does receive less than it sends with regards to direct money, according to the Commission’s own calculating method for 2013.

But the European Commission argues that access to the single market is another obvious economic benefit that far outweighs the physical payments, although referring to an unspecified UK government analysis.

Ok, but by leaving the European Union, we could save £135 million then for, say, our NHS?

Experts and observers have actually started debating more about how much the NHS will lose because of Brexit.

In short, this is because the NHS is already under strong financial pressure and increasing demand – without Brexit. Add in the Brexit factor and it is mostly thought to get worse, as a recent report by the UK in a Changing Europe highlighted:

Decreased economic growth and productivity following Brexit means less tax money available, for the NHS and any other public service. Depreciation following the referendum means more money is needed to buy required imported products.

As the NHS is highly dependent on EU staff to fill ever-increasing vacancies, tightened immigration rules towards Europeans is likely to worsen the issue

Authors are also concerned about the future of public health in the UK, as much of the progress in that direction rather came out of European Union policies. Fears are that “domestic commitment to such policies will be weakened in the future.”

A study published in The Lancet in September 2017 listed the issues the country’s health system is likely to face with regards to either a soft, hard or failed Brexit.

By soft Brexit, the authors mean leaving the EU without losing most of what the single market brings in economic and regulatory benefits to the UK. Hard Brexit is a situation in which a new free trade agreement (FTA) would be the next step following the failure of negotiating a soft Brexit.

Finally, a failed Brexit means exiting the EU would result in no special follow-up agreement between the UK and the EU, meaning it would rely on existing World Trade Organisation rules which would offer the UK no special access or privilege from European countries in most regards.

As the authors explain, a new FTA would be the most time-consuming option, stretching the Brexit-generated uncertainties by up to a decade, as trade agreements can take years to negotiate.

Here is a summary table of threats to the NHS as explained and synthetised by the researchers.

This is broad and of little meaning to me and my family’s daily lives. How can we observe any difference from our point of view?

Simply put, the NHS will simply have an even harder than at the moment to deliver its services to the population, because of decreasing funding and recruiting.

A critical issue is the lack of staff supply.

The report from the UK in a Changing Europe stresses that the demand for staff will only get higher as the supply is expected only drop even more following Brexit. In other words, there won’t be enough staff in the NHS to take care of everyone anytime soon – which means longer waiting time, less focused care and staff that are increasingly experiencing high stress and pressure.

More recently, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has been pressuring the government to establish clearly whether EU workers within the NHS will be able to stay after Brexit. This comes as new figures still show an increase in EU leavers of the NHS workforce, a trend the Nursery and Midwifery Council (NMC) observed in last November as well.

EU workers have already been less numerous in joining the NHS workforce last fall and more have been leaving, in England as well as in Birmingham.

EU workers have already been less numerous in joining the NHS workforce last fall and more have been leaving, in England as well as in Birmingham.

“It feels that efforts to boost the number of nurses are being dragged down by a botched Brexit,” said Janet Davies, Chief Executive at the RCN in a statement on April 25.

“Nurses returning home, or giving Britain a miss entirely, are doing so because their rights are not clear enough. Theresa May must use every opportunity to say they are welcome here and valued in health care.”

“As the overall number of nursing staff falls again, it is patients who will worry the most. The Government knows patients can pay the highest price when staff shortages bite.”

In October, an analysis conducted by the RCN showed there was a shortage of 10,000 nurses in mental health specialisation only, and 40,000 for all specialisations.

Staff shortage and ever-increasing demand for supply was already a major issue before Brexit

The UK did not exactly need Brexit to experience a shortage of health workers. It has had this problem for quite a while now.

In a report by the OECD in 2015, using data from 2010-2011, it was shown that the UK was among the most reliant on foreign-born doctors and nurses, respectively at 35% and 22% of its workforce.

This might be because, the same report shows, the UK is also among the top exporters of health workers in the world, and at the top 1 or 2 among OECD countries.

It is estimated that, in 2010-2011, the UK had more than 50,000 nurses working abroad, making it the top exporter after India and the Philippines. For doctors, the figure was around 17,000, after India, China and Germany.

In New Zealand in 2011 and 2015, British nurses were the largest foreign-born group of nurses at respectively 10% and 8% of the local workforce. They were the second biggest foreign-graduated group of nurse practitioners in Canada too, after the Philippines for most of the 2007-2016 decade. As well, British and Irish nurses were the largest foreign-born group among the nursing workforce in Australia in 2011.

It is not hard to see why working abroad seems like a great option for many health workers, if we compare the wages here in the UK and the cost of living to those of other similarly rich countries, as the chart below shows:

Almost everywhere else than in the UK, the nursing staff is financially better off. The workers earn more in the context of a cheaper cost of living.

This would not be so much of an issue if the workers considered they were paid a fair amount of money for what they do.

But it is not the case.

In last November, a survey conducted by the RCN revealed that many nurses are in fact struggling financially, and some even feel the need to work another job to make ends meet, or leave the profession altogether. These trends increased significantly in recent years:

“Of the members who responded to the survey, 70% reported feeling financially worse off than they were five years ago, while 24% say they are thinking of leaving their job because of money worries.

The percentage of respondents who say they are looking for a new job has also increased from 24% ten years ago to 37% today.

And 61% say their job band or grade is inappropriate for the work they do, a significant increase on the last survey in 2015, when only 39% said this was the case.

As a result of these severe financial and workload pressures, nursing staff are now less likely than at any point in the previous 10 years to say they would recommend nursing as a career to others – only 41% said they would do so this year, compared with 51% in 2007.”

In March, the government did agree on a pay raise for the NHS staff affecting 1.3 million workers, especially for those earning less. While half of the staff will see a rise of 6.5% within three years, some workers will receive up to 29%. Nurses with one-year experience with receive a 21% rise over three years, increasing their annual wage at £27,400.

While more money is coming, understaffing is still an issue that money may or may not resolve. Another survey in September 2017 reveals that 36% of nurses had to leave necessary patient care undone in their last shift, 65% said they worked additional time, of which 93% of those in the NHS claimed they were not paid for this extra hour (average). The RCN estimates this extra unpaid time is worth £396 million annually.

It was recently estimated for the account of the NHS itself that the health system is short of no less than 100,000 staff. A month earlier, in January, data from NHS Digital obtained by the BBC revealed that no less than 33,000 staff have been leaving the workforce last year. NHS leavers have now surpassed the joiners.

So was this promise for the NHS any reasonable? What the different parties have said and are saying at the moment?

Campaigners and members of the government have been more silent, or else, embarrassed by this promise not very long after the outcome of the referendum.

Merely an hour after the Leave victory in June 2016, key campaigner and UKIP Leader Nigel Farage acknowledged that this promise was probably a mistake and cannot be guaranteed, and stated that if he had to think it through again, he would probably have chosen not to promote this.

In the following September, the Brexit camp, now known as the new pressure group Change Britain, abandoned all references to the NHS, simply talking now about broad areas of interests that could receive the saved fundings.

In a TV interview in March 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May refused to say where any prospective saving from leaving the EU would go, and politely acknowledged that during the referendum, “there were points made, often very passionately on both sides of the argument […]”.

“We will be, as part of the negotiations, we’ll be ensuring that we’re not paying those significant sums in the future”.

During the Brexit campaign, an opinion survey polled NHS leaders and revealed that virtually no one saw any potential benefits in most aspects of leaving the European Union. 80% of them worried about staff recruitment, and that it could jeopardise funding for research and innovation.

Some of them only said that it could have a positive impact on the procurement and competition rules affecting their trusts.